Why Focus on Vision?

Our photography is elevated to an art form to the extent that it reflects our internal vision. The technique is important to the extent that it allows us to manifest that vision in a tangible manner accessible to ourselves and others. Technique and vision intertwine but they are not the same thing. Look at the great photographers, you admire. What you will find is a consistency in their work that is unique to them because it reflects their personal vision. I have known many photographers who take beautiful photographs with excellent technique, but who feel unfulfilled and unrecognized because they have not yet found that vision.

So much for theory. How do we find that vision? How do we create photographs which are uniquely our own and which allow others to say “aha. I recognize that as a [insert your name] photograph?” This can be the most challenging and frustrating aspect of maturing as a photographer but in the end it is (for me at least) the most satisfying. What follows are eight steps we all can take to find that vision. These are not intended to be a simple sequence or checklist. They are concrete things all artists can do to find that vision, to nurture it and it give it an opportunity for growth.

It is possible to learn technique from others through study and emulation, but that is merely the parroting of someone else’s vision. In the end we can stimulate discovery of our own through a number of simple exercises which have been very helpful to me through the years. What follows are some specific suggestions which I hope may be helpful to you.

Table of Contents

Expose your self to the works of many visual artists and become familiar particularly with those whose work appeals to you on a very basic and emotional level. What images excite you? Move you? Remain in your mind long after you stop looking at them? This entails looking at photographs as well as painting and sculpture. For me this list has included photographers like F. Holland Day, Edward Steichen (Steichen at the National Portrait Gallery) Paul Strand, Robert Frank, Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus, Sally Mann and Jock Sturges, as well as painters including Rembrandt, Vermeer, Edward Hopper, Balthus and the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi.

But that “short list” is personal. You need to create your own.

If you go through this exercise I would urge you not to rely solely on images off the Internet. I certainly don’t mean to exclude this as a source for your exploration, but don’t make it your exclusive reference point. Visit museums and galleries. Go to the best libraries available to you. Art schools, colleges and universities often have extensive collections of books and photographs available to you. Some museums will allow you to examine and hold original works of other artists, giving you an opportunity to appreciate the more subtle characteristics of the image. For example, the Tate in London has a terrific collection of photographs that can be examined in person. Other museums have similar programs. Go to openings at galleries and museums. Listen to the artists, gallerists and other attendees discuss the works on display.

Recognize that looking at these images is an important part of your work as a photographer, and therefore deserving of significant time.

As you begin to narrow your list of inspiring artists and images, analyze what you find appealing in their work. Is it the psychology? Their use of light? Their use of color? Is it the subject matter in particular that holds your interest? Are you able to identify an image you have not seen before as (for example) a Paul Strand photograph? How so?

If you haven’t started a collection of photography books, do it now. Begin with five monographs of photographers (or painters) whose work you love. Study them. Read about the lives of the artists. Then study them more. Look for those elements in their work that makes it distinctively theirs. Try to understand how that artistic work intersected with their lives. These insights can be invaluable as you chart your own course toward a personal artistic vision..

As you come to terms with your own response you will develop insight into your own emotional connection to their work. You will also begin to see exactly how the artist has developed a style that reflects her vision. This is a key component of discovering the vision you want to express in your own photographs.

At this point you may wish to experiment with your own photography, learning the techniques that will allow you to emulate the elements of your favorite artists. When I was beginning as a portrait photographer I consciously spent two years photographing a number of models in the styles of several photographers whom I admired. I found this very helpful because it gave me some structure around which to develop technique. As I went through this exercise I became aware of the particular challenges and nuances of the vision and technique of those other artists. However I had to be ever mindful that success duplicating those styles was not an end in itself but only a means towards the development of my own personal vision and style.

Workshops and classes in photography can be extremely helpful in the development of technique. However, in my experience it is unusual for a workshop to offer the kind of inspiration in vision that I am speaking of. Too often I have seen workshop instructors unconsciously stifle the development of vision and students by pushing their own technique and vision upon their students. Fortunately there are some exceptions to this phenomenon.

I was blessed by taking a workshop with Jock Sturges almost 20 years ago. He was a teacher who understood his role in nourishing the private vision of the student. But I suspect that my experience was the exception that proves the rule. Nonetheless, I would encourage you to attend workshops and take courses, but when you do be careful to keep your eyes open. Be mindful that you may have to resist pressure from an authority figure who will try to make your work conform to his or her vision rather than promote your own.

Let me give you an example. A friend of mine (who is an excellent photographer in his own right) was a teaching assistant at a course taught by a very well known and revered photographer. I am a great admirer of the photographer in question. But as the course proceeded and the students showed their work, the teacher would heap praise upon the students whose work resembled his own. The work that did not meet this “standard” was not remarked upon at all. The message was clear. The good photographs were the ones that reminded the teacher of his own work. This could be a very destructive experience for the creative student who lacks confidence. Remember this: You own your vision. No teacher is entitled to belittle it, whether by outright criticism or by silence. And the quality of the teacher’s photographic work is not a measure of the quality of the teaching.

Find good mentors and editors who share your passion and whose eye you respect. These folks don’t need to be photographers. In fact it is sometimes preferable to find mentors who are not photographers; this minimizes the possibility that the mentor’s own sense of competition may negatively impact his ability to give you good feedback. Most importantly, if you have good mentors and editors who truly want you to succeed, you may be less inclined to isolate yourself out of fear that your will hear negative comments about your work. We all need “tough love” — candid criticism of our photography but not destructive undermining, no matter how subtle. There are many good examples of photographers benefitting from great mentors.

Most photographers I know are not good editors of their own work. For me, it has been the insight of my wife and a gallery curator that have been the most accurate in identifying my best work.

Here is an exercise that has worked well for me through the years: Create the book from your own work that you would like to buy. Make the subject matter something you love. I photograph, print and edit a body of work comprised of 40 to 80 photographs that I would love to find on the shelf in the bookstore. One benefit of this project is that it focuses me on what I love and where my passions are, rather than succumbing to the temptation to make work to please an external audience.

As you create your book you can begin to focus on the myriad of variables that will link your photographs to one another. How do these photographs hold together as a collection? How do they speak to one another? Do they allow the viewer to move through the book in a manner that holds her interest? Is the toning (black & white) or choice of color harmonious throughout? Is the unifying theme captured in all the photographs? Pay as much attention to the sequencing of the images as you do with their initial selection. Be brutal as you edit and include only those images that you are truly happy with and which serve to round out the book. You may have some great images that don’t fit. Leave them out. You may have to reprint some images several times to get them truly consistent with the others.

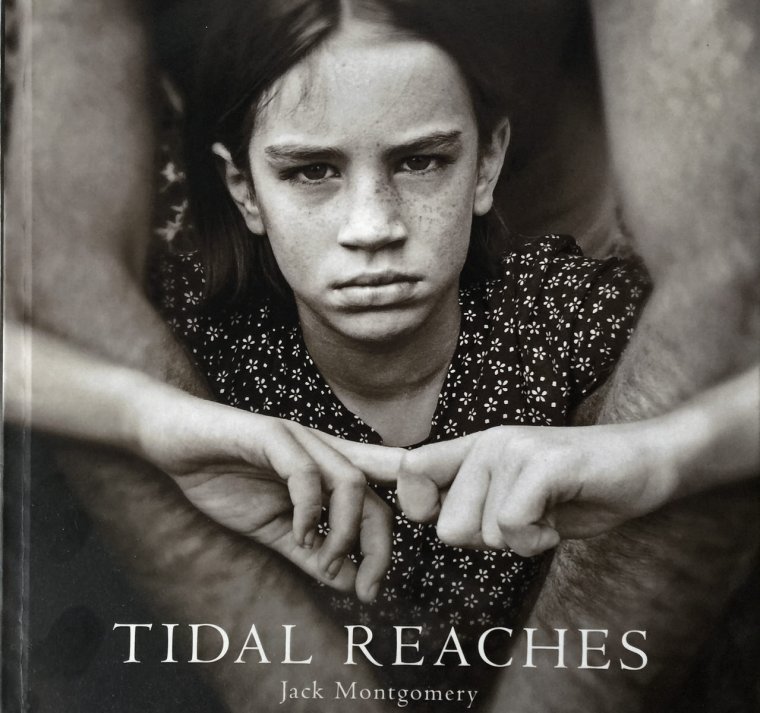

These days you have the option to have the book printed at a reasonable cost, though be forewarned that taking it to that next step is a significant technical challenge if you are going to achieve the best result. After creating several “books” I took the plunge and hired a designer/editor to help me go the next step. While never submitting it for publication, the exercise (including the insights of a professional designer) was very helpful in refining my personal sense of vision. (Many of the photographs in the Tidal Reaches “book” were ultimately published in a reedited monograph.)

What you will be left with is the outward expression of your vision. That vision will evolve but it now exists. And it is yours alone.

Learn about struggles of other photographers and artists as they searched for their vision. One of the most compelling examples I have read in several years is Sally Mann’s autobiography Hold Still. Her own life experiences have been almost gothic and a rich source of her imagination.

She is very articulate as she links her photographic vision back to her early life, to the region in which she was raised, to literature including her own writing and other elements. (For example, “…[T]he relationship between my writing and photography has never been clearer to me than it is now…”) Hold Still, p. 206. Whether you are an admirer of her photography or not (I am), the book is a compelling read and it drives home the point: our vision is a reflection of our experience. Its roots are in our personal psychological and spiritual makeup.

“I began to see my artistic life… as the inevitable result of my silent father’s clamorous influence”. Hold Still, p. 402

You can follow the trajectory of her photography on her website, dating back to her earliest photographs. Sally Mann website. This is an excellent opportunity to see how her vision has evolved through decades marked by a changing subject matter. Yet the images hold together on a level deeper than the subject. Her photography is also greatly informed by literature. Sally Mann: By the Book Few of us will achieve Sally Mann’s level of insight nor her level of accomplishment. But most of us will benefit by increasing our understanding of what is fueling our photographic endeavors and then using those insights to hone our vision.

Don’t become discouraged. Don’t expect the process to go quickly or easily. In fact for the truly great artists, I admire, the evolution of that personal vision lasts a lifetime. But once you have found that vision — no matter how elusive or dynamic — it will become your most prized possession as an artist. It is well worth the struggle to find it.

Further Reading: Alain Briot, “Developing your Vision”

Comments (0)

There are no comments yet.